Lonnie King: From Lunch Counters to Freedom

By Shiloh Gill

As a young 22-year-old college student, Lonnie King knew that there were problems in his society that could not be ignored any longer. He wanted to make a difference, not just for himself, but for everyone. With a thought, a few willing students, and almost reckless determination, Lonnie King helped turn Atlanta inside out.

The AU Center has always been a citadel of higher learning for African-Americans and

there is no reason why we should be left behind

- Lonnie King

After seeing four young college students spontaneously start lunch counter sit-ins in Greensboro, North Carolina, King knew that they were on to something. While the fire was still raging in Greensboro, King believed that it was a perfect time to start another fire in Atlanta.

However, unlike the sit-ins in Greensboro, he didn’t want spontaneity. He believed a well-planned protest was the best kind of protest. Almost instantly he began planning and thinking about how he could start not just a protest, but a movement. With friend Joseph Pierce and reluctant newcomer Julian Bond, Lonnie King started working to organize students from all the schools of the Atlanta University Center (AU Center). However, much to the chagrin of the presidents in agreement, Dr. Harry V. Richardson (Interdenominational Theological Center) and Dr. Frank Cunningham (Morris Brown College) decided they sided with the students. Astonished by this turn of events, the well-spoken Lonnie King explained their case.

However, much to the chagrin of the presidents in agreement, Dr. Harry V. Richardson (Interdenominational Theological Center) and Dr. Frank Cunningham (Morris Brown College) decided they sided with the students. Astonished by this turn of events, the well-spoken Lonnie King explained their case.

To him, it was simple why the students needed to fight. He stated that “The AU Center has always been a citadel of higher learning for African-Americans and there is no reason why we should be left behind.” He wanted equality and a life that did not consist of feeling less than any person, anywhere.

However, much to the chagrin of the presidents in agreement, Dr. Harry V. Richardson (Interdenominational Theological Center) and Dr. Frank Cunningham (Morris Brown College) decided they sided with the students. Astonished by this turn of events, the well-spoken Lonnie King explained their case.

To him, it was simple why the students needed to fight. He stated that “The AU Center has always been a citadel of higher learning for African-Americans and there is no reason why we should be left behind.” He wanted equality and a life that did not consist of feeling less than any person, anywhere.

After some time of discussion, they came to a compromise that required the students to write a list of grievances. It would be a document detailing why they felt a movement was necessary and what they were fighting for. This was a step that King felt was “a way to get the students so involved in writing the document that they would leave the actual doing to someone else.” This proved not to work.

The start of the Atlanta Student Movement, as it was coined, was an exciting outlet for many students seeking reformation. However, it didn’t come without opposition. One evening, Dr. Mays, the president of Morehouse College, assembled the rest of the presidents of the AU Center to have a talk with the student leaders.

Dr. Mays being somewhat opposing, had assembled what he considered a united front. Dr. Rufus Clement (Atlanta University), Dr. Albert Manley (Spelman), and Dr. Brawley (Clark) were all present in the meeting. Dr Brawley, in conjunction with most of the other presidents, had even told the students that if they decided to go downtown and participate in any sit-ins that they would bring embarrassment to him.

With all this stacked upon them at one time, Lonnie King was determined to address this insult to their movement, fearlessly.

Soon after the meeting, the students did as they were asked. King assembled a team, composed of English majors, to write the document asked for by the opposing presidents. A manifesto was soon written by Spelman Student Body President Roslyn Pope, entitled, “An Appeal for Human Rights.”

Once it was finished, the students under the leadership of King continued their planning of demonstrations for freedom. Gathering three student leaders from all six AU Center schools, King had designed an unstoppable force. His well spoken ability proved to be quite a selling point to all, instantly gaining him support from every school through the students.

In a one-on-one interview I conducted with King, he described, “knowing exactly what they were going to do, we had the manifesto as our roadmap.” The same manifesto the presidents requested gave direction to the students and began to further their movement. By March 15th, six days after the manifesto was published in the Atlanta Journal, Atlanta Constitution, and the Atlanta Daily World, the students began their sit-ins.

King was working non-stop preaching nonviolence and the need for strategy. He said he believed “in working with your head, not your fist. We understood that the one thing that would hurt them the most was their money.” The students did exactly that. They targeted ten different lunch counters, which in turn would slow the flow of white customers and cause the businesses to lose money. As a student of economics, King believed that the power of money would cause a business to change their practices.

After 200 students got arrested on March 15th at various lunch counters across Atlanta, they were more determined than ever. Larger crowds of students were willing to risk arrest for freedom. King, stating the dangers to crowds of sometimes 2000 students or more, knew that he had to be a thoughtful leader.

As people were arrested, and experienced the hardships of the movement, King believed that they needed to target a bigger fish. After other sit-ins, he decided to do a “test-run” at one of the biggest stores in Atlanta. One day in June 1960, King sat-in at the prestigious Magnolia Room, located upstairs in Rich’s Department Store.

That day he went with Spelman professor, Dr. Howard Zinn and his family. Usually Dr. Zinn, a white man, wouldn’t have been turned away, but this day he was. King and Zinn’s family were not only turned away but detained.

King recalls being sent to a place separate from Zinn and encountering Dick Rich, the Vice President of Rich’s, waiting. In an exchange between the two of them, King recalled Rich saying to him that “he was tired of me, and that he would put my black a** in jail.” To this insult, King responded, “I will be back Oct. 19th, with full troops ready for another sit-in there.”

From that moment on, King continued as a battleship of change. He went on to do exactly what he said, and on Oct. 19th held the famous sit-ins at Rich’s. This date would become the most historic in the movement. King had convinced then rising civil rights leader, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., to participate.

Everyone was arrested, including Rev. King, and this afforded the students widespread publicity for the cause. His arrest went on to gain national attention from presidential hopeful, John F. Kennedy. Kennedy and his brother were integral in King being released from jail. It is said that the single action of helping King, caused the turn of the 1960 presidential election. The clergy along with the black community were persuaded with a document entitled “the blue bomb” to ensure Kennedy the win.

Without the willingness and selflessness of a 22-year-old college student named Lonnie King, none of this would have taken place. Single-handedly, he stood for what was right before he was sure if anyone else would stand with him. The sit-ins, protests, and demonstrations he organized would forever impact the city of Atlanta and the United States. The desegregation of lunch counters in the Fall of 1961 was just one of many victories for Lonnie King. He would go on to continue to fight for civil rights for decades to come. His life is a testament to what determination, belief in the betterment of humanity and unity can bring.

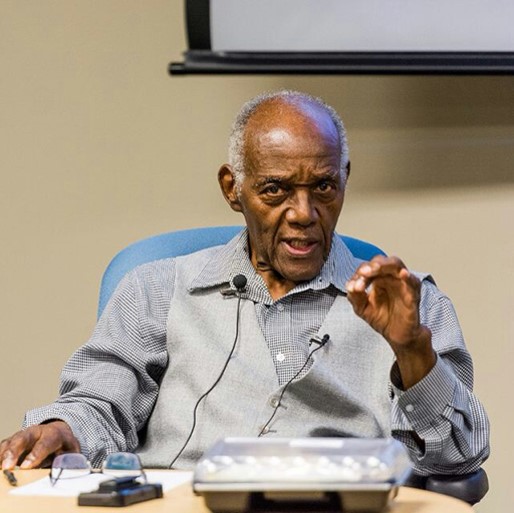

In 2016, King continues to be a visionary. With plans for human rights organizations in colleges, opening more charter schools for those in underprivileged neighborhoods and working on his dissertation, there is no limit for him.

He also continues to mentor those in similar civil rights movements today while teaching non-violence and peace. With a recent visit to Kennesaw State University, he took the time to talk with students and said that he “came to life again” and “loves talking with students because they are the future change of this country.” Lonnie King is a public servant who has made this world better, and now he says “it is our turn.”

Let us continue to fight for what is right.