Historical Groups

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) played a pivotal role in the Civil Rights Movement, uniting young activists committed to achieving equality through nonviolent resistance. Alongside other key organizations, SNCC's dedication and courage sparked widespread protests and inspired future generations to continue the fight for justice and social change.

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)

By Margaret Henderson

They saw the change that needed to happen and took it upon themselves, knowing that their lives were at risk, to make the change that others simply talked about.

Mr. King explained the way the group formed and went into detail about the fact that this group was made up of a number of private, black college students.

They were educated and knew better than to sit by and continue to be treated the way they were. They knew that it was not right both socially and morally to be physically separated from the white community in any situation.

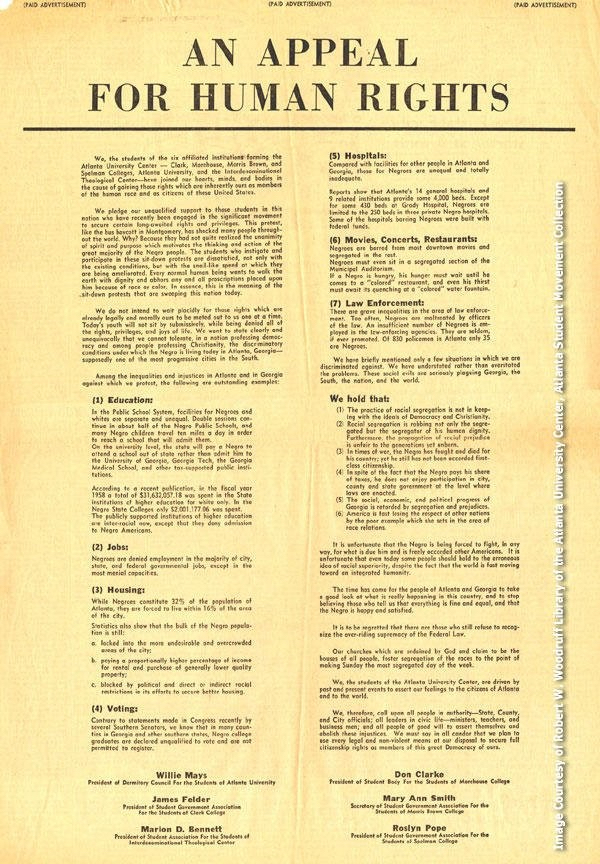

When the time came for the newly formed activist group to make their mark, they knew that it must be handled in a strategic way. Lonnie King assigned Ms. Roslyn Pope to compose a document that would simply explain the reasoning behind their movement.

I believe that it can be argued that had the Appeal for Human Rights never been written, published, and circulated in the manner that it was, the sit-ins would not have made near the impact that it had. This document set the tone of what they were so avidly fighting for.

This group of early twenty-year-old kids forever left their mark on the world. They saw the change that needed to happen and took it upon themselves, knowing that their lives were at risk, to make the change that others simply talked about. SNCC is admirable for creating a movement that did not rely on the need for violence or acts of stupidity to get their point across. Instead, they used their intelligence and with to go forth with their dream. A dream of equality.

The formation of this group was not so blacks could sit with whites at a lunch counter. It was the principle of the issue that they were not seen as equal to everyone else around them. They were viewed as a lower class human beings and that they did not have the God-given rights that every other white person habitually had.

This group still inspires so many people. There is an extreme need for a new group like SNCC to come forth and make a difference in the world. People today are too concerned with themselves and the notion that they cannot make a difference in the world. We have gotten to this mindset because people today believe that if they partake in a social media post with a given hashtag or Facebook profile picture that they are helping in a big way.

Because of SNCC and their actions, they were a huge stepping-stone on the path to equality No. This is not how it works. It takes the passion and conviction that Mr. Lonnie King emulated to my classmates and me as he spoke about his experiences. Perhaps this means that we do not use social media outlets as a place to vent or go on long rants. Instead, we need to use them as a platform for people to unite and plan on ways to come together to make those differences in the world!

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee is a group of people who need to be recognized as national heroes. Because of SNCC and their actions, they were a huge stepping-stone on the path to equality. It is easy to say that we are still walking along that path , but I believe it is the young people and students of the world that have the potential to make the greatest difference. If we look at SNCC, we have a brilliant guide to finish the walk on the path!