Cooking with Rare Books: Recipes from "The English Housewife"

KENNESAW, Ga. | Oct 30, 2020

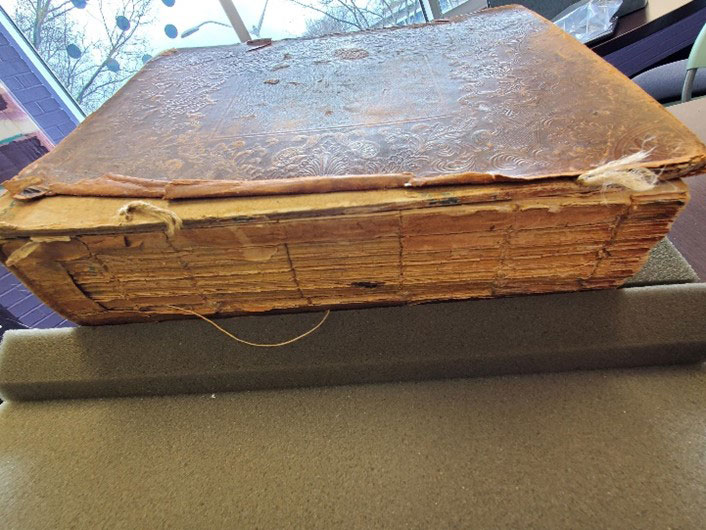

KSU senior Camilla Stegall interprets recipes from Gervase Markham's "The English Housewife" (1631).

Hello everyone! We are going to explore a few recipes featured in Gervase Markham's The English Housewife.

While reading these recipes a few words can stand out as almost alien to modern readers. These include: Verjuice and Sippets. Thankfully, The Foods of England Project has wonderful explanations for these words and other historical cookery words. Since these are prominent in the upcoming recipes, here are their definitions.

Verjuice is an acidic juice of sour grapes, crab apples or other sour fruit and was used much like we use vinegar today both in recipes or as a condiment. Sippets are like an early form of crouton. Small pieces of bread served with soup or meat and usually dipped into gravy.

In addition to new words, when reading The English Housewife, one cannot help but notice some interesting spellings in the text. This is a highlight of reading the recipes today. As we look at the recipes, some quoted words will be presented as spelled in the cookbook. There is even some variation in spellings throughout the same recipe.

The recipes included in The English Housewife from 1631 were not presented in the way that we present recipes today. The recipes are set in paragraph form, with usually vague instructions on how much of an ingredient to add and how long to cook things. Some of this would have been acquired knowledge through cooking, but still very different from the detailed step-by-step recipes we have today. The recipes themselves ranged from simple meals, that could be easily be prepared by housewives, to more extravagant dishes, such as you might see at a banquet. Below, I’ve summarized a few recipes that are similar to dishes we cook today:

“A fine Boyld Meate” is a prime example of a simple recipe in the English Housewife. You get your “foure pecces of a racke of mutton” and wash them and put them in a clean pot. Then you get a “good quantity of Wine and Verjuice” and sliced onions and put them into the pot to boil with the meat, for “a good while.” Later you will put in sweet butter, ginger, and salt. Finally, you will thicken the broth with grated bread and “serve it up with sippets.”

Whereas “A fine Boyld Meate” is simple, “Olepotrige” is extravagant. It is “the onely principall dish of boild meate which is esteemed in all Spaine.” You will need an exceptionally large pot for this recipe. Fill it with water and put it onto the fire. Then put in “thicke gobbets” or chunks of beef. When the beef is about half done, put in potatoes, turnips, and skirrets (another type of root vegetable). At this time, you can also put in mutton and pork. When this mixture has cooked for a while put in venison, veal, goat, and lamb. A bit later, add more meat and this time some vegetables including spinach, lettuce, scallions, marigold leaves and flowers, violet leaves, and strawberry leaves. Later add a partridge, chicken, quails, blackbirds, sparrows and “other small birds.” When these poor birds have cooked, it is time to season the broth with a “good store of Sugar,” cinnamon, ginger, cloves, nutmeg mixed with verjuice and salt. Make sure to stir the pot well before serving. You will want to serve Olepotrige on long dishes with lots of sippets. Once it is on the long dishes, cover all the meat with dried fruit and almonds, cover the fruit with orange and lemon slices, put roots on the side, “and strew good store of sugar over all, and so serve it foorth.” (You can make a more simplified version of this recipe today, “Olla podrida.”)

The difference between these two recipes highlights the disparity in what people in early 17th century English society ate. The wealthiest could eat several courses at one meal, which could include rare birds and venison, which was a status symbol because only wealthy people could hunt deer. The middling classes would eat something more like the “Fine Bolyd Meate” and it would be prepared by the housewife rather than a French chef. The poorest classes would have the least access to meat (Mortimer 2012, 247, 254-255, 258-259).

If you have ever cooked any form of fried dough, Markham's recipes for “The Best Fritters” and “The Best Pancakes” will sound familiar to you. For the fritters, beat eight eggs, taking out four of the whites, and a pint of cream with spices, including cloves and nutmeg. Then add “two spoonful of the best Ale barme,” which will be used as a leavening agent, and salt. Once this is mixed, “make it thicke according unto your pleasure with wheate flower.” Then leave it to rise by the fire. When the batter is risen, boil sweet oil over the fire. When it “beginnes to bubble,” put sliced apples into the batter, and put this mixture by spoonfuls into the oil until they are “crispe and browne.” When they are done “throw good store of Suger and Cinamon upon them…and so serve them up.”

For the pancakes, beat two or three eggs and add them to “a pretty quantity of fair running water” and beat them together. Once beaten, added the spices, such as cloves, cinnamon, nutmeg, and some salt. Like the fritters, add as much “Wheate-flower” as you want. “Then frie the cakes as thinne as may be with sweete Butter,” until they are brown. Serve them with sugar on top. Markham adds that some people make their pancakes with milk, but he believes that “makes them tough, cloying, and not crispe, pleasant, and savoury as running water.”

As we can see, these are very similar to how we make these dishes today. Simply put, humans love fried dough, and the process to create it has barely changed in 400 years. In addition, we can see the importance of spices and sugar in the recipes. These would have been prominent ingredients in both wealthy and middling households (Mortimer 2012, 255). The English love for sugar was almost insatiable.

If you would like to see the Pancake Recipe recreated, Lynne Fairchild recreates Markham’s recipe along with two older pancake recipes in this video. Fairchild begins cooking Markham's recipes at the 10:31 mark.

For more information on The English Housewife and Food and Drink in Elizabethan England:

Ian Mortimer. 2012. The Time Traveller’s Guide to Elizabethan England. New York, New York: Viking

Best, Michael R., ed. 1986. The English Housewife. Kingston, Ont.: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

The Foods of England Project - http://www.foodsofengland.co.uk/index.htm