KENNESAW, Ga. | Dec 10, 2020

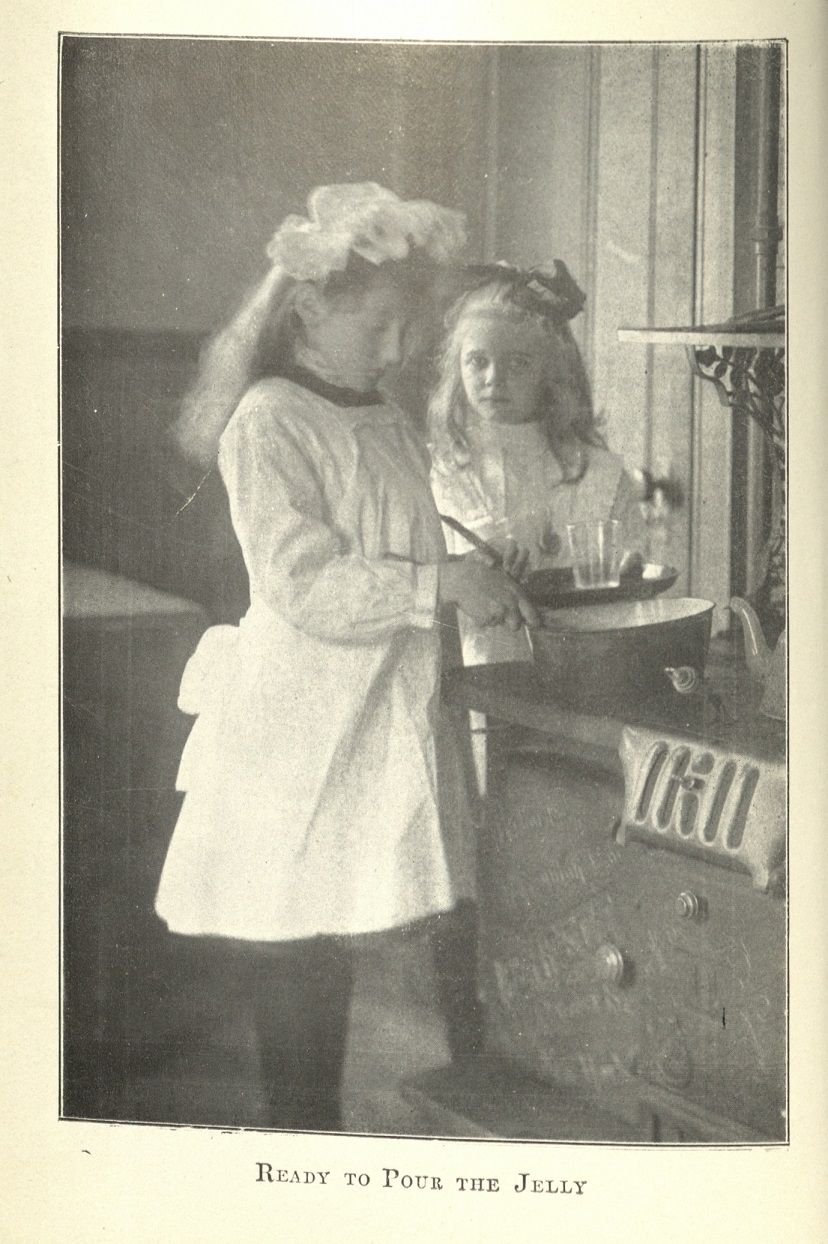

KSU senior and archives student assistant Caitlin Hobbs breaks down the historical context and culinary delights of "Cookery for Little Girls" by Olive Hyde Foster (1910).

Hey y’all! Welcome back to our little Cookery Corner! I’m Caitlin Hobbs, filling in for Camilla this time around. I’m a senior at KSU as well, getting my degree in anthropology and am the student assistant for the archives and rare books department! No worries, you’re in some good hands this week. If there’s one thing I know, it’s food and history, and that’s definitely something covered in this post about Cookery for Little Girls.

Now Cookery for Little Girls was written by Olive Hyde Foster and initially published in 1910. This date lands it towards the end of the Progressive Era (1896-1916) of United States history. This time is marked by a significant focus on social activism and political reform. Prohibition was ramping up support, as was women’s suffrage. Scientific management, where the scientific method was applied to management to increase labor productivity and efficacy, was becoming popular. This was a time of muckraking and showing corruption amongst the upper echelon and growth and strengthening of the middle class. People, especially women, were interested in moving away from the domestic values of the Victorian Age. This is also when eugenics starts to get a foothold in the United States, and the origins of birth control, but that’s a conversation for another time.

During this time, women (white, wealthier women) were pushing for more rights. Using municipal housekeeping language, they were able to push for reforms of rights across the country like prohibition and women’s suffrage. They were forming clubs to talk about these new-to-them ideas of equal rights. But during all this we find books like Cookery for Little Girls, which still hold to those old Victorian values. This is an instructional book for women who are teaching their daughters how to cook, host a party, and become a good wife. These skills were of the utmost importance because, according to Hyde, “nothing is really more pitiable than the helpless woman who, when occasion demands, finds herself unable to do ordinary cooking” (Foster 1910, Preface).

The book is notably aimed towards those of middle-to-higher class, especially with recipes calling for veal cutlets and lamb, and extensive menus for holiday feasts. For instance, the Christmas menu suggested from the book consists of raw oysters, roast goose, apple sauce, celery, mashed potatoes, lima beans, tomato jelly salad, plum pudding, and coffee. The book is still representative of traditions from the time period Foster grew up in, and it should be viewed as such, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s bad. Leaving old traditions takes time, especially something as deeply ingrained in Western gender roles as “women do the cooking and manage the house and children.”

To its merit, the text does a pretty good job of helping parents instruct a child in the kitchen. Hyde is aware of what children would be capable of, what they shouldn’t do by themselves, how to construct a menu and shopping list with them, and what order the recipes should be done in when preparing for a party or large feast. Going back to the suggested Christmas menu (because that’s why y’all are here), Foster starts off by telling you to get the plum pudding cooking first. For good reason, a good plum pudding takes about four hours to cook properly. And no, it’s not pudding the way we think of it in the Snack Packs. Plum pudding has its origins in medieval England, so it is boiled/steamed in cooking and is more cakey than anything else. It also doesn’t have plums in it, sorry. “Plum” was just used when referring to any type of dried fruit, but especially raisins in the Victorian age.

Moving on, you make the apple sauce next, so it has time to cool. There’s not much to say about this recipe; it’s just your standard apple sauce, made without the convenient electric hand blender we have now. After making your apple sauce, you make oysters. Well, “make.” You’re serving the oysters raw, over ice. Which, I'm sorry, I know I'm biased here as I greatly dislike oysters in any form, but I cannot get past serving raw oysters. If you like them then you can have my share.

Finally, for the last recipe, Foster tells you how to make the tomato jelly, which is exactly how it sounds. You boil down tomatoes, an onion, celery, and some cloves, strain them, add some gelatin in cold water to the strained liquid, and let it set in molds overnight. It’s a simple recipe but is indicative of a coming change in food trends.

How does that relate to a tomato jelly recipe in a cookbook for little girls and their mothers published in 1910? Well, this era is where that gelatin craze starts. Like I mentioned, you need to refrigerate gelatin to allow it to set. If you don’t have some sort of a refrigeration unit in your house, or the money to have one, you can’t work with gelatin. Plus, in 1845, unflavored dried gelatin was beginning to be sold, making it easier to attain. No more do you have to boil old hooves for your gelatin, ladies! But here you have recipes being written for those with the access (read: money) for easy refrigeration and ready-to-use gelatin, that those who don’t have that access have to look at and watch others enjoy. And wonder. So, in 1950, when the United States hit the point where over 80% of households have a fridge, household cooks didn’t have to wonder anymore. They could test it out for themselves.

From tomato jelly, Foster goes on to help you keep your color scheme, like putting catsup in the oysters, making sure your holly is ready to be a centerpiece, and allowing your daughter to set the table herself for good practice.

If this, or Olivia Hyde Foster’s other books, were being published now, there would be some definite side eye going on with how it suggests getting your daughter ready to manage her own household and be a good young wife when she gets married. Even at the time it was published, it was a little dated, but not as much as one would think. And you know, being able to work and cook in a kitchen is a necessary life skill for everyone. I just wish this also included teaching your sons to cook. But well, this is the 1900s y’all. Can’t be perfect.

That’s it for this year! We’ll pick back up after the new year with more about rare books and cooking!

For more info on the Progressive Era in the United States, or the effect of refrigeration on society, check out the sources below.

Foster, Olive Hyde. Cookery for Little Girls. The Premier Press, 1910.

Kraisner-Khait, Barbara. “The Impact of Refrigeration.” History Magazine - The Impact of Refrigeration, 2020, www.history-magazine.com/refrig.html.

“Progressive Era.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 26 Nov. 2020, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Progressive_Era.